At The Union, we work for a lot of different clients, across a lot of different industries. But whether we’re trying to make people social distance during lockdown, buy more bottles of whisky, donate blood, or save for their pension; at our core, there’s one underlying purpose: we’re looking to change people’s behaviour.

The challenge then, is how do we do this in the most effective way? We carry out surveys, asking consumers what they think or how they feel, and there’s a lot of value in doing so. But inevitably, we can run up against a key issue:

Consumers don't think how they feel. They don't say what they think and they don't do what they say.

David Ogilvy

In short, we lie all the time; both to others and to ourselves. It’s human nature.

One way we can combat this tendency for mistruths is through applying findings from behavioural science research to our campaigns, an approach I learnt about recently on a fascinating IPA course run by behavioural science author and consultant, Richard Shotton.

So join me as we take a whistle stop tour of three lies that I, as an average consumer, tell myself; the research that reveals the truth behind my behaviour; and the potential ways in which we as marketers and advertisers can apply this research to the benefit of our campaigns.

Lie 1 – I march to the beat of my own drum

Alas no. I’d like to think I’m an originator, but given my average day features Curel Skincare (‘Japan’s No.1 Skincare’’), Costas (‘for coffee lovers’), and a Marks and Spencers meal deal (‘this isn’t just food…’), it’s pretty clear I follow the crowd. The good news, at least, is I’m not alone. Following the majority in our behaviour is something most if not all of us do, and we might not even realise we’re doing it. This phenomenon is known as social proof, and it can be a powerful tool to use in campaigns.

The Research - Throwing in the towel

We all know it’s better for the environment if we reuse our hotel room towels. Less washes mean less resources used; but sadly for hoteliers (and the planet), people still throw perfectly clean towels out for laundering. Psychologist Robert Cialdini and fellow researchers worked with an American hotel chain to see how social proof could impact towel reuse, creating door hangers with three different messages for guests.

The control door hanger, which read, “HELP SAVE THE ENVIRONMENT. You can show your respect for nature and help save the environment by reusing your towels during your stay.”, led to 35% of guests reusing their towels.

The second hanger leveraged social proof in, “JOIN YOUR FELLOW GUESTS IN HELPING TO SAVE THE ENVIRONMENT. Almost 75% of guests who are asked to participate in our new resource savings program do help by using their towels more than once.” This led to 44% of guests reusing their towels, an uplift of 9%, purely by indicating that towel reuse was the popular, majority action.

When this social proof messaging was taken one step further in the third hanger, stating that most guests who stayed in that specific room chose to reuse their towels, towel reuse rose to 49%, which Cialdini noted could be due to the hanger being more relevant to this particular audience.

Perhaps most interesting of all though was Cialdini’s follow-up to this study. When he asked another focus group what messaging might motivate them to reuse their towels, the vast majority selected the environmental message – the opposite of reality.

So, how can we use social proof in campaigns?

It might seem simple, but the first step could be ensuring consumers understand how popular a product is. We might know, but the public might not. Carling, for example, is the UK’s top selling lager, but in a study by Richard Shotton, only 24% of consumers surveyed were aware of this.

Even if the product isn’t market-leading, there’s bound to be an element that shows the product’s popularity. Whether it’s in units sold per week, leading a subcategory, or sales growth, creatively expressing this popularity could drive more consumers to buy.

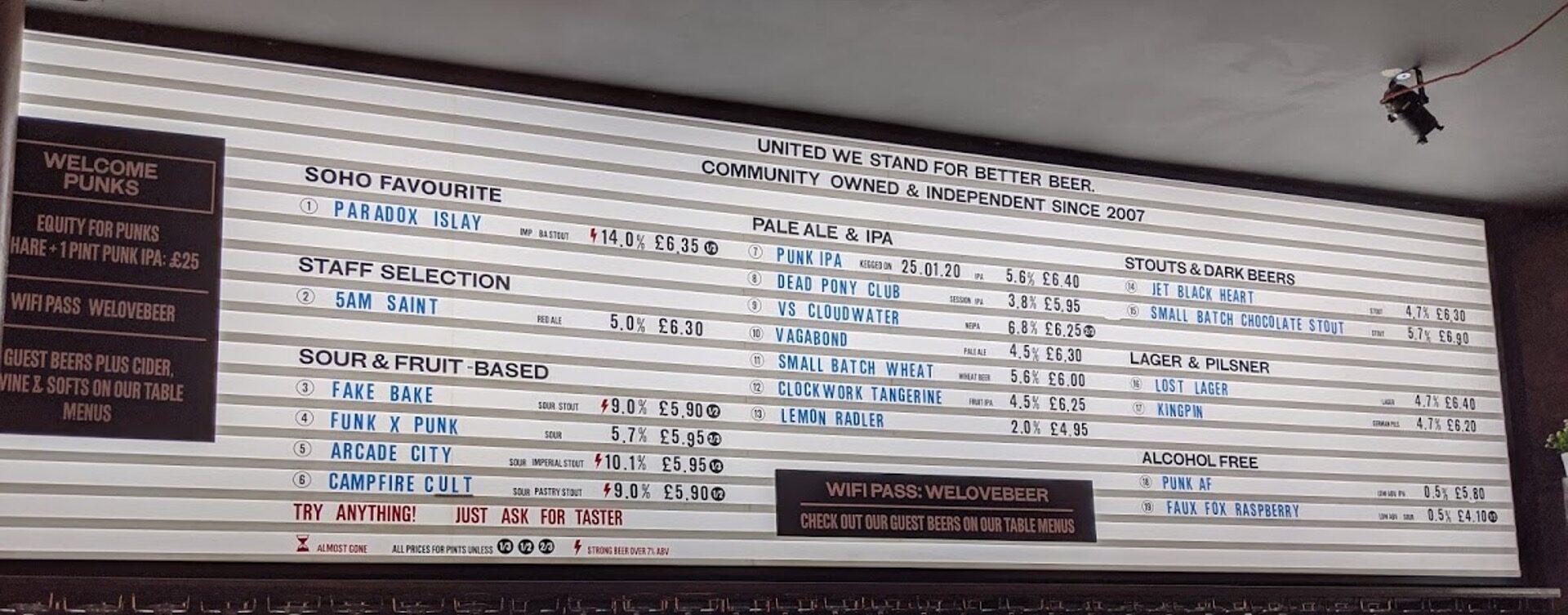

A second step could be following Cialidini’s lead by making the claim of popularity relevant to a specific audience. This could be through targeted regional advertising, like the below example from BrewDog which shows the most popular, (and through pure coincidence I’m sure, most expensive) beer in their Soho bar:

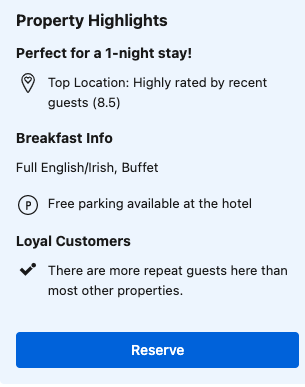

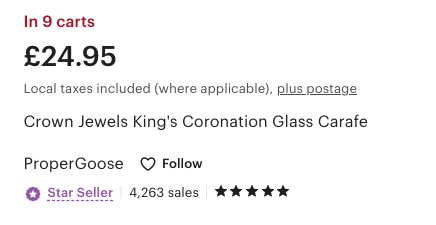

Targeted social proofing can also be extended to the internet as practised by Booking.com, which demonstrates the popularity of particular hotels through notes on repeat guests and by Etsy, which shows how many other consumers are lined up to buy a particular item, stacking FOMO onto popularity to drive purchases.

Lie 2 : I always do the right thing

Again, sadly, no.

Sure, I’m not robbing banks or arson around. But in lots of little ways, I’ve shown I’m not the greatest – I’ve forgotten to show up for a doctor’s appointment, spent rather than saved, and again, I’m not alone.

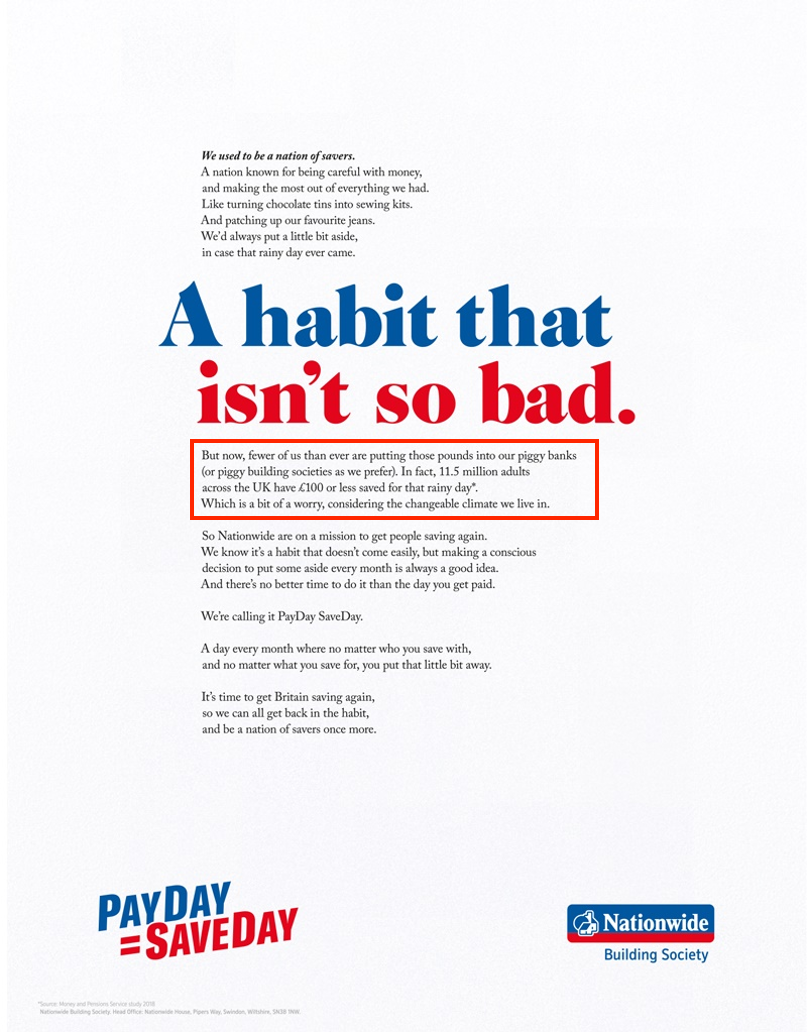

If I were a truly good person; I’d look at these well-meaning campaigns and think about how I need to do better. But studies show that these types of campaigns can have the opposite of their intended consequence. It gives negative behaviour a veneer of social acceptability.

So instead of changing my ways, I can keep missing doctor's appointments and book a holiday rather than sticking the money in savings, because hundreds of thousands of people are doing exactly the same thing. This is known as negative social proof, and the impact of leveraging this can be startling.

The research – Hot wood

At Arizona’s Petrified Forest National Park, tourists can visit an ancient village, see the badlands, and apparently steal as much petrified wood as their grubby little hands can hold.

With a tonne of wood walking out of the park every month, Cialdini (yep, him again) and fellow researchers decided to investigate whether negative social proof messaging could have an impact on the behaviour of sticky-fingered tourists; mapping out three areas of the park with signage designed to elicit different responses. This led to some pretty interesting results.

The control area, which had no messaging at all, saw a theft rate of 2.9%.

The second area, which politely condemned theft in the message, “Please don’t remove the petrified wood from the park, in order to preserve the natural state of the Petrified Forest.”, saw a theft rate of 1.7%

The third area, which leveraged negative social proof in its messaging, “Many past visitors have removed the petrified wood from the park, changing the natural state of the Petrified Forest.”, saw a staggering theft rate of 7.9%. That’s four times the levels experienced by a simple message reminding people not to steal, and double the rate where there was no messaging at all. And why? Because the messaging gave theft social acceptability. Everyone was doing it, so what the hell, let’s steal some wood. In Cialdini’s own words:

This wasn’t a crime prevention strategy. It was a crime promotion strategy.

So, how can we use negative social proof in campaigns?

Where we’re faced with negative statistics or behaviours as part of a campaign, one option could be to flip it around, emphasising the good behaviour instead of the bad.

This was used to great effect by NHS Blood and Transplant in this donation campaign.They could have talked about people who haven’t donated at all or who do not donate regularly, giving people an insight into how the majority of people do not donate regularly. But instead, they focused on first-time donors in Sheffield, stacking positive emphasis with targeted positioning:

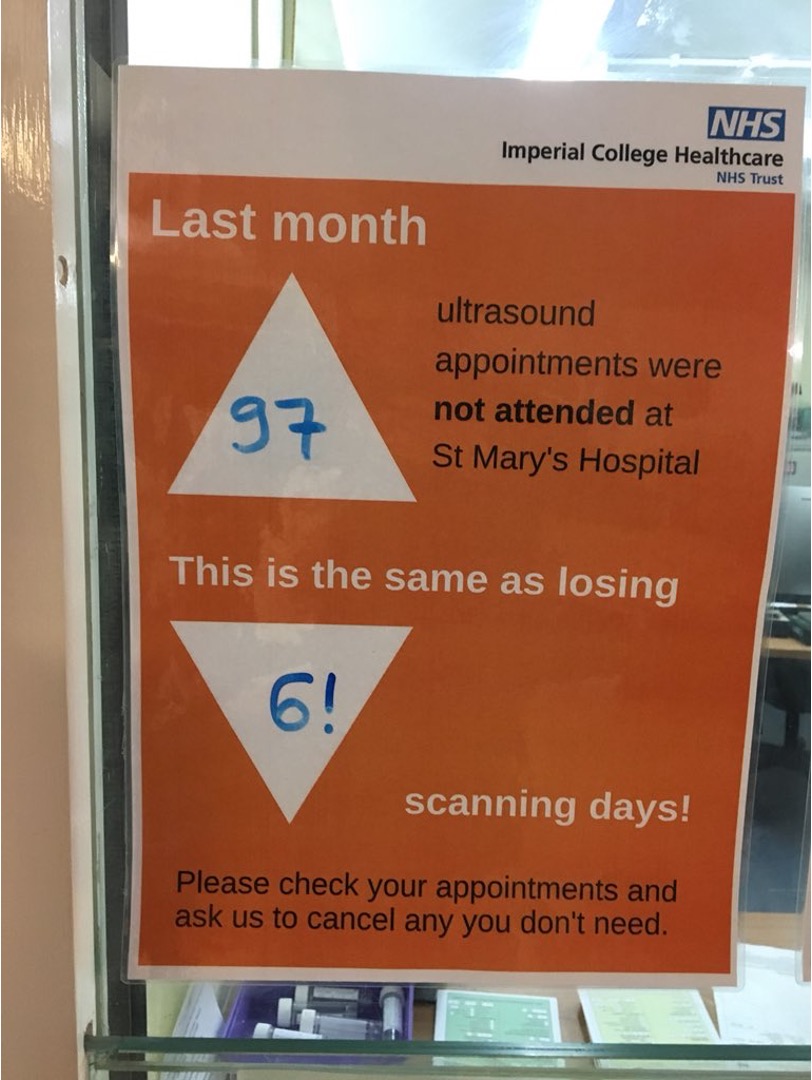

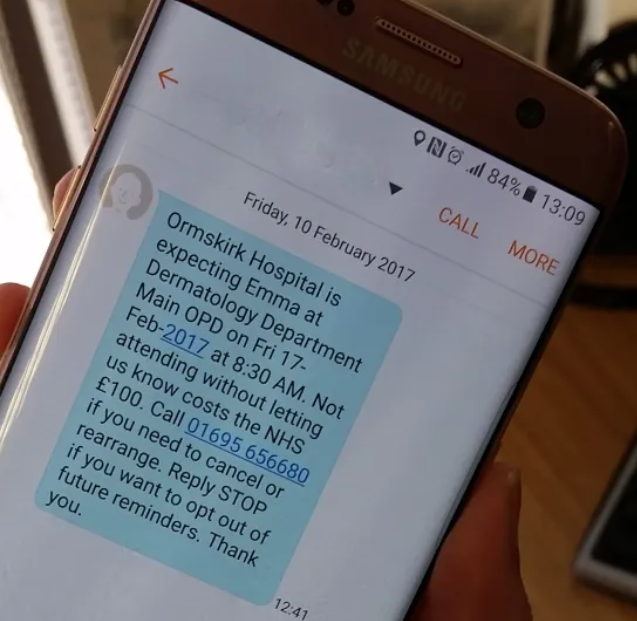

Another option could be to express the consequences of undesired behaviour in a different way. Rather than condemning a large, faceless group of patients who failed to attend their appointment, Ormskirk Hospital chose to instead show patients the cost of a single failed appointment to the NHS in £s through appointment reminder texts, which research has shown to be a simple yet effective way to reduce no shows.

Lie 3 - I put the effort in

To the colleagues reading this, I try, honestly I do, but sometimes it’s just so much easier to take the lazy option.

Case in point, recently I cancelled an online transaction just because they didn’t take PayPal and my card was… somewhere, still not sure. I could have gone and found it, but it would have taken effort, and I valued sitting down more than whatever I was going to buy.

Fortunately, I have it on good authority that I’m not the only one. Nobel Memorial Prize Winner Daniel Kahneman says:

A general ‘law of least effort’ applies to cognitive as well as physical exertion. The law asserts that if there are several ways of achieving the same goal, people will eventually gravitate to the least demanding course of action… Laziness is built deep into our nature.

Kahneman argues that the most effective way of changing behaviour is to remove friction or small barriers, and the research agrees.

The research – Signing up is hard to do

Back in 2017, economics professor, Peter Bergman, and behavioural scientist, Todd Rogers, carried out some research on the ease of signing up for educational support, randomly sending a group of parents one of three text messages:

The Standard Text let parents know they could sign up for the support service via a website, and led to a 1% sign-up rate.

The Simplified Text let parents know they could sign up if they replied “Start”, and had an 8% sign-up rate.

The Automatically Enrolled Text let parents know they’d been automatically enrolled but that they could opt out by texting “Stop”, and had a 96% sign-up rate. Parents didn’t opt out even when given a simple way to do so.

So, how can we work to remove barriers in campaigns?:

We could try putting ourselves in a customer’s shoes, and identify how many barriers there are between the customer and our desired end goal.

When visiting a website, do they need to click through lots of links to get them to where they need to be? If so, is there a way to simplify this journey? Amazon’s ‘1-Click checkout is just one of the ways the firm has worked to remove as many barriers as possible between customers and purchase. And though we might hate Netflix’s autoplay feature, it’s made judgement-free binge-watching that bit easier.

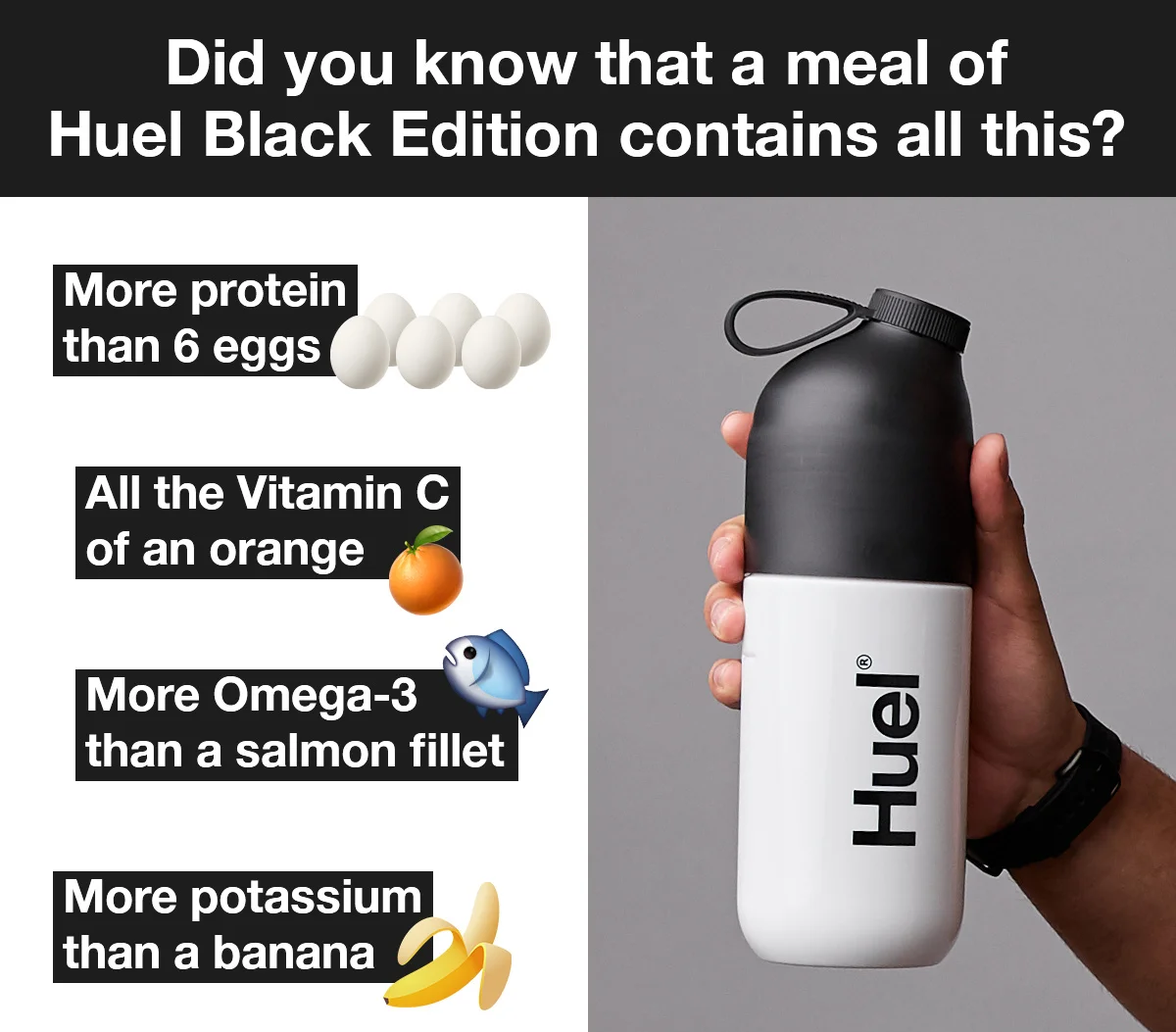

We could also look at whether product benefits can be quickly and easily processed by consumers. Like Huel, who frame their nutritional benefits in a way that’s much simpler for customers to quantify than typical measurements like grams.

In conclusion

If behavioural science is the answer to bypassing our own tendency to lie, we have to wonder why we aren’t basing campaigns on research all the time. Well, the appetite to use these tools has to be built in from the start, and as Shotton says:

The insights from behavioural science won’t sway everyone, all the time. They just increase the probability that communications have the desired effect.

But even if behavioural science isn’t a one-size-fits-all magic wand; if we’re willing to put in the time, testing and experimentation, we may find that paying attention to the potential power of leveraging social proof, negative social proof and barrier removal is to the benefit of our campaigns.