Change is in our DNA

We are an integrated marketing agency that believes in effecting change for the benefit of our clients and society through the seamless weaving of insight, data, innovation and creativity.

Latest work

Business to Business

Utility

Retail

The champion of transformation

ScottishPower

View case study

Education

Health

Public Sector

Changing more than nappies

Scottish Government | Parent Club

View case study

Retail

Sponsorship

Ace the schuhlace

schuh

View case study

Health

Public Sector

Getting the nation back into donation

SNBTS

View case study

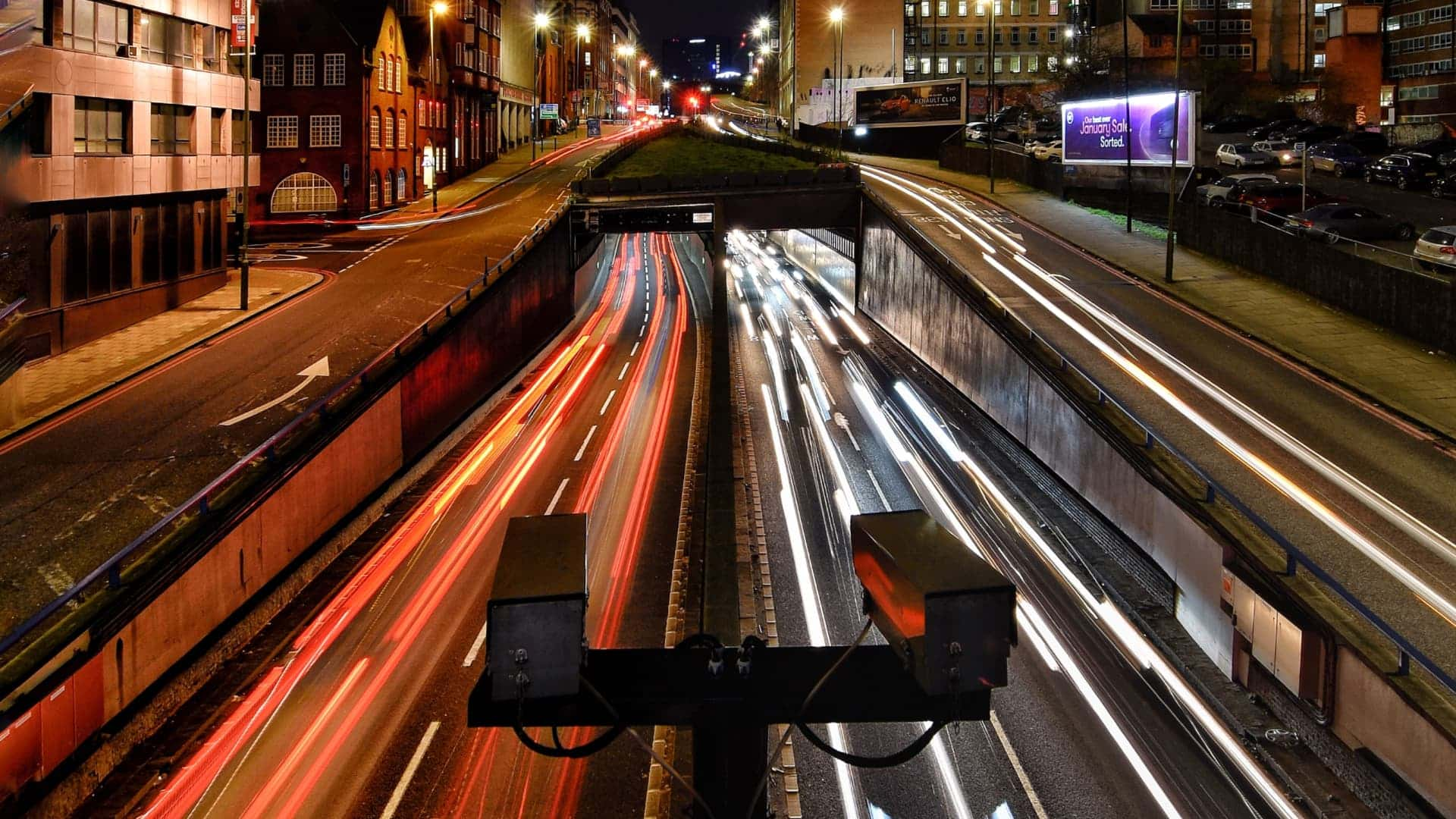

Public Sector

Transport

For the journey

Traffic Scotland

View case study

The Union group

To accommodate the minutiae of any given challenge, and the respective talents required, we are comprised of five specialist units right here in Edinburgh.

Be part of the Union

Got grand career ambitions? Hello. Have a peek at our careers page, and see if there are any current vacancies that tickle your fancy.

Up for a change?

We’ve only just met and here we are enquiring after your status. Brazen. You probably want to do a little more browsing before making any commitments. But if not…